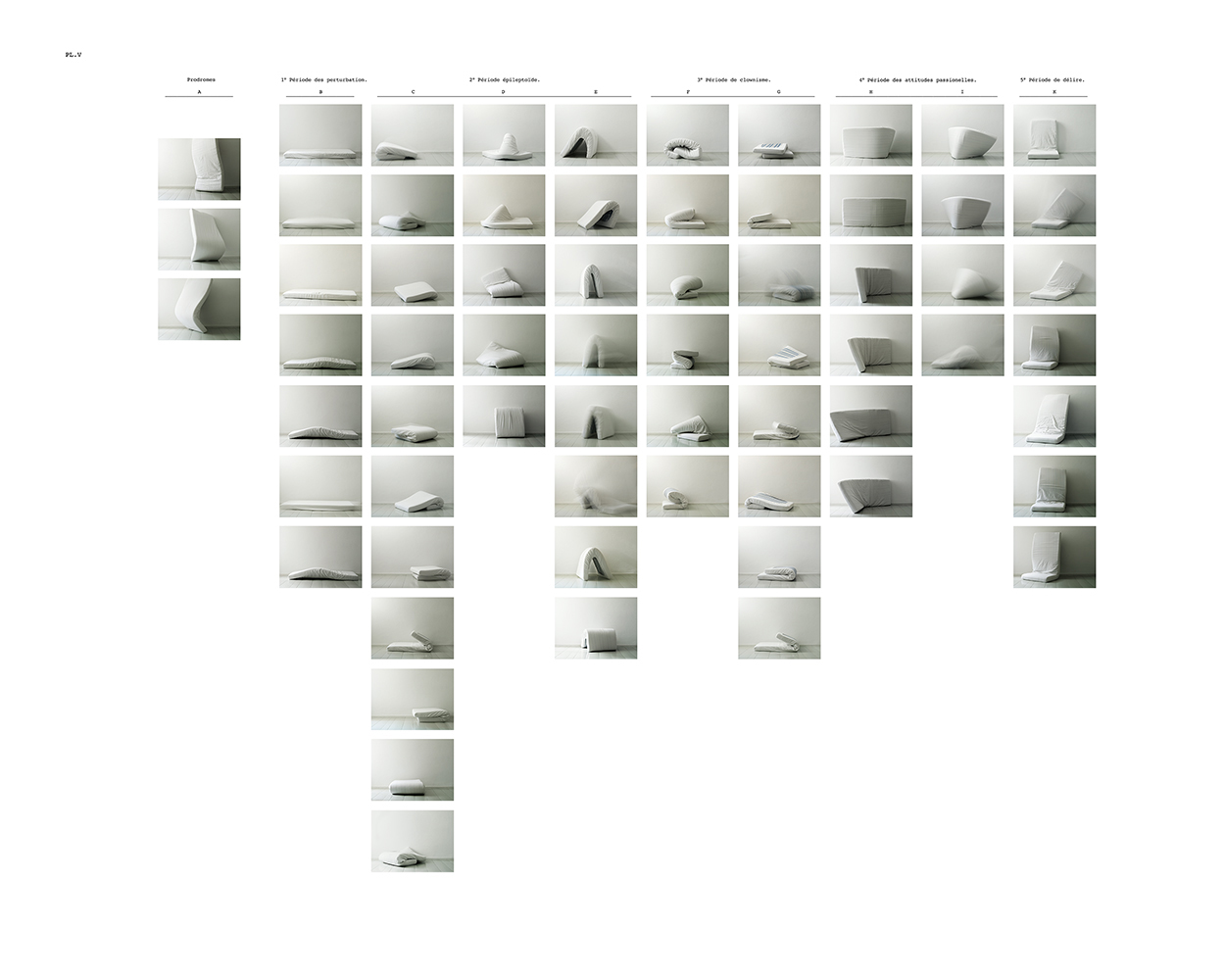

attitudes passionelles

This work in an homage to Paul Richer's "Tableau de la synoptique grande attaque hystérique complète et régulière' positions typiques et avec variant"' from 1885. It is a graphical clinical tableau modelled on Jean Martin Charcot's photographs.It shows the various stages of a hysterical attack on the example bodily demonstrations of a young woman. The "real" photographs in the drawings were modified to fit the panel and still the panel was officially considered as clinical evidence of the symptoms of a disease that no one could actually define. The "real" hysterical attacks, performed by actors which followed instructions, and then photographically "documented".

What I find particularly fascinating while looking at various photographs from the late nineteenth century, is the obviousness that hysterical women almost exclusiveley suffered their hysteria on mattresses.

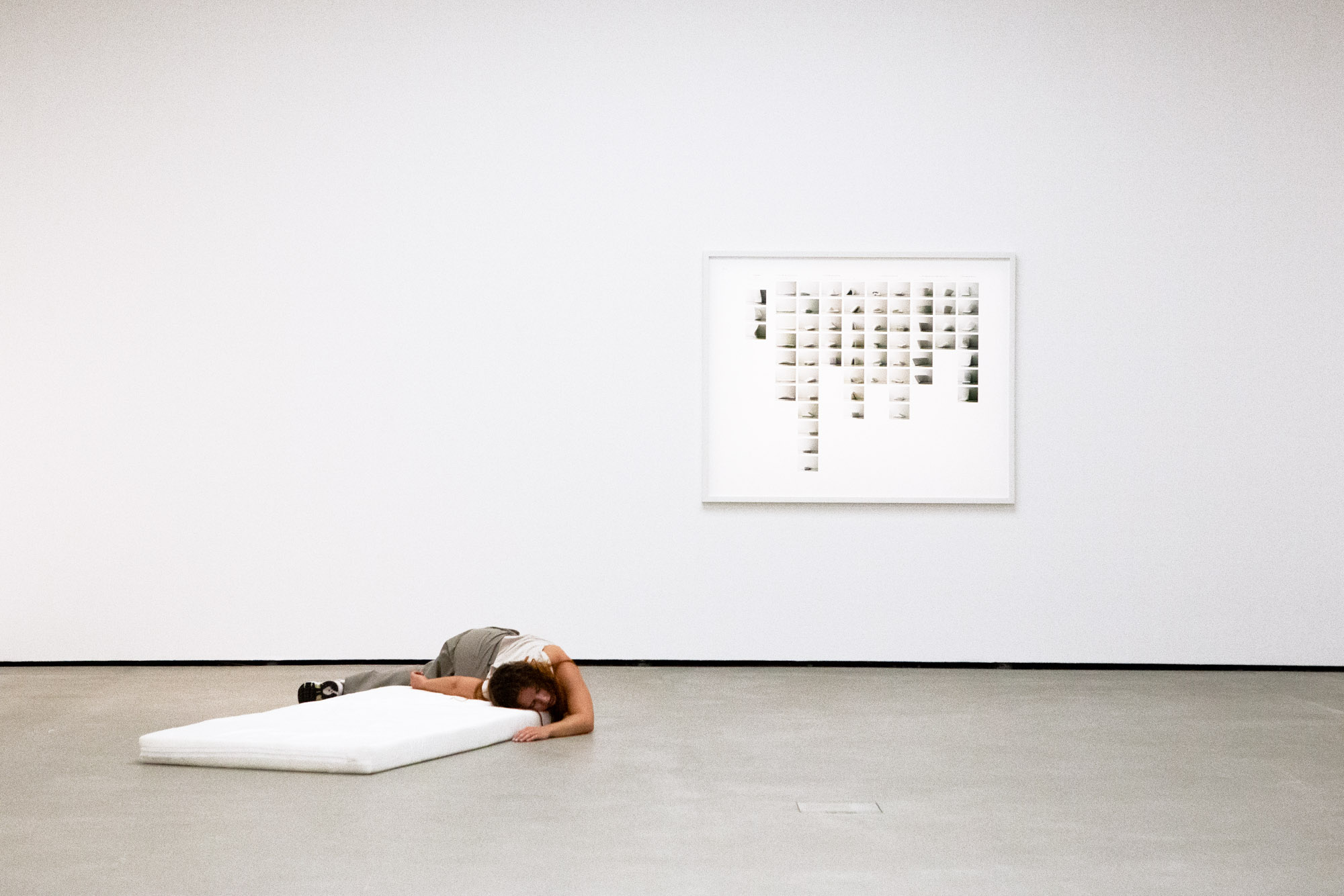

In these pictures, the mattress is always a kind of counterpart of the actual patient. Especially in Rummos photographs, which in turn were intended as an homage to Charcot, the mattress gets a life of its own under the acrobatic efforts of the woman in the striped one piece. It seems as if the mattress imitates the hysterical attacks.

In my tribute to Paul Richer's work, the mattress alone becomes hysterical.

7-part sequence, 60x80cm, matte diasec, edition of 5 (+2AP)

Tableau, 120x150cm, inkjet Fine Art print, framed, edition of 3 (+2AP)

Museum der Moderne, Salzburg, performance by Bodhi Dance Project

performance along my works by Mai Ishiwata at Phönixhallen, Hamburg, 2014

deleting babiński

Valerie Schmidt's work “Deleting Babiński” can be understood as an intervention in the pictorial dispositif that Georges Didi-Huberman describes in “Invention de l'hystérie” as the creation of a tableau clinique: an orchestrated arrangement in which the female body is not simply viewed, but transformed into a symptôme visuel through the mechanisms of seeing. André Brouillet's painting „Une leçon clinique à la Salpêtrière“ (1887) serves as a paradigmatic document of this dispositif. It shows Charcot's theatricality in the production of truth, his staging of hysteria as an image that is less diagnosed than performatively produced. The patient Blanche (Marie Wittman) appears in it as the embodiment of a ressemblance—not of an individual suffering, but of an aesthetically and medically produced image formula. The moment of fainting—that moment of “withdrawal” and theatrical surrender into the arms of the male doctor—is both image production and power production.deleting babiński

The eight-part photographic series dissolves this historicized visual structure by isolating the falling female figure and transforming it into a sculptural body form. The moment of transition into unconsciousness—or rather, the moment in which this transition is performatively depicted—is frozen by the photographic interruption of movement. The poses appear rigid, but they have emerged from a highly dynamic sequence; they oscillate between loss of control and choreographed gestures of collapse. In this way, the work refers to the historical visual practices of hysteria, which systematically shaped the female subject as an aesthetically prepared symptom carrier: as a body exposed to seeing, searching gazes.

The medical invention, aestheticization, and popularization of hysteria in the 19th century produced a symptomatic iconography in which women are depicted almost exclusively as suffering, powerless beings in need of rescue—always framed by male authority, expertise, and control. This pictorial tradition not only stabilized clinical power relations, but also functioned as a cultural foil that linked femininity with vulnerability, excess, and irrationality.

Schmidt's work subverts this structure by removing the male support from the picture, thereby destabilizing the epistemic foundation of historical representation. In her case, the protagonist now supports herself; the once functional male hands now appear only as obscure, almost decorative residues that can neither protect nor control. This overturns the iconographically established gesture of powerlessness: it transforms into a paradoxical pose of autonomous imbalance, a form of self-assertion in the moment of supposed loss of control.

Deleting Babiński is therefore not only a critical rereading, but also an epistemic counterpoint to Brouillet's tableau clinique. The series transforms the iconographic tradition of hysteria from a space of male authority to a place of visual instability and knowledge production. It shows that the hysterical image—the image of the body sinking to the ground, seemingly without will—is not complete, but open to new montages, new meanings, new formulas of pathos. In this sense, Schmidt works entirely in the spirit of Didi-Huberman: she does not leave the historical image to rest, but makes it tremble.

fig. 1-8, 2014, series of 8 flags, 350 x 243,5cm, Multiflag

also as an edition of Hahnemühle barita prints, 18x24cm, edition of 5 (+2AP)

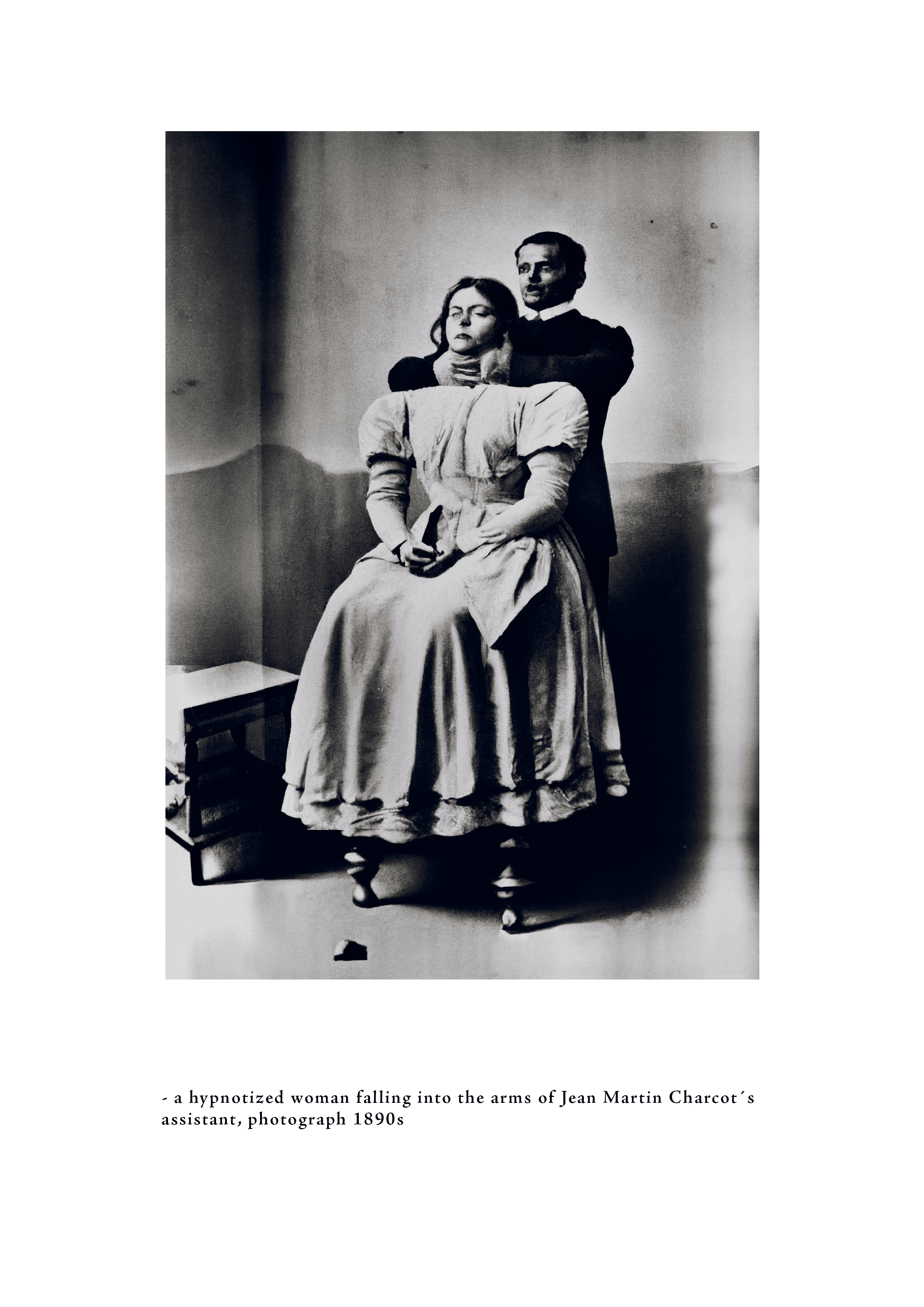

”choked by AI”

For this set of AI-based photo-like imagery, I worked with artificial intelligence and this prompt:

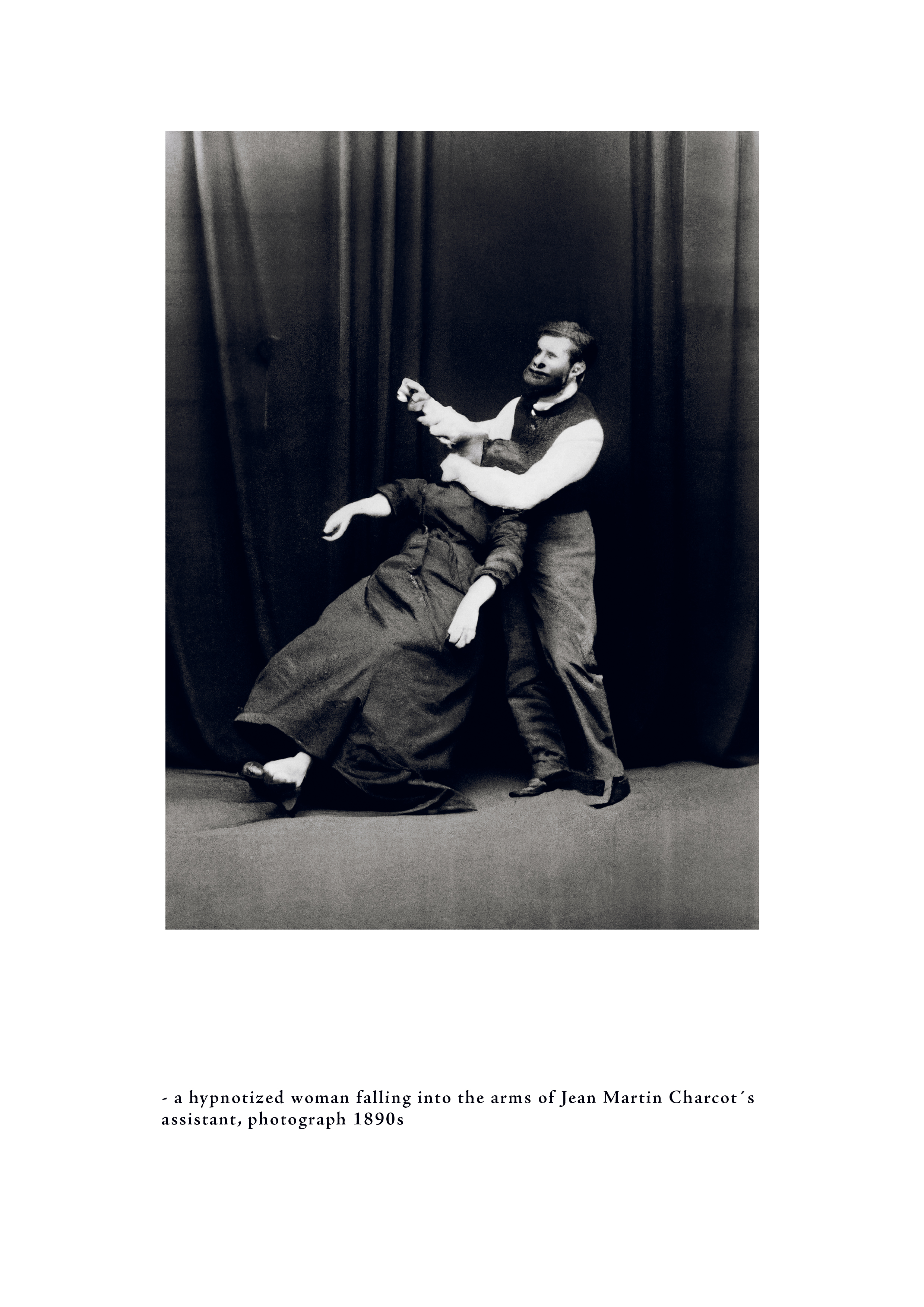

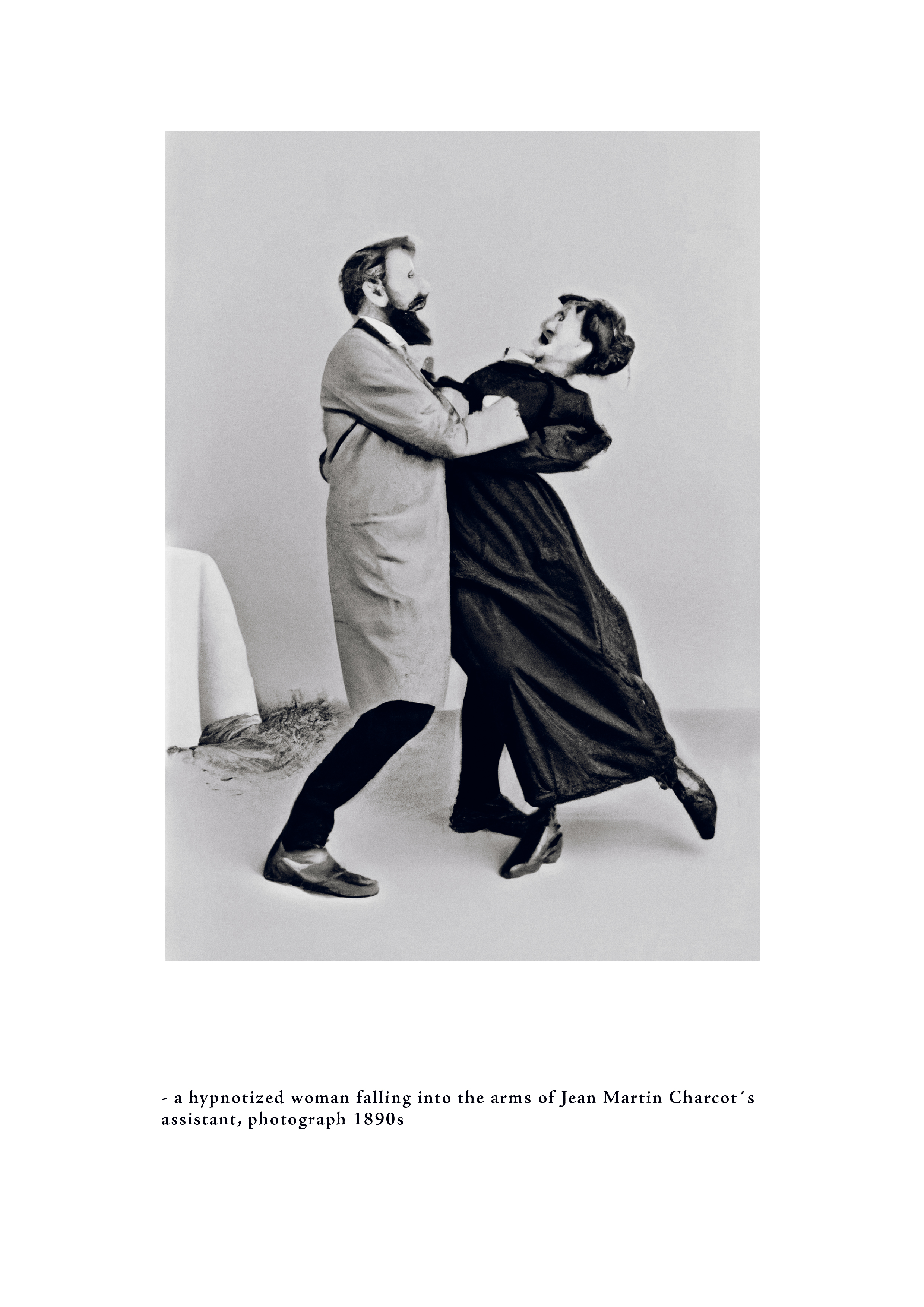

- a hypnotized woman falling into the arms of Jean Martin Charcot´s assistant, photograph 1890s

The disgorged square image, was then expanded via ”outpainting“ to create a scene instead of working with an excerpt only. I chose 10 images which all depicted a violent scene, in which the docotor attacks or strangles the female patient.

How does automatic image censorship trained by human eyes and human conscience work, if the machine apparently independently concocts brutal scenes through traditional images of supposedly credible photographic results? Do humans as viewers then have to report back these image results, do we as ethical beings have to teach the machine that such scenes are unacceptable and unacceptable? Is it possible that we might still be the better judges of what is or isn´t visually appropriate?

Does the AI act like a socially priviledged person, who has an idea of technology and culture that is appropriate to his social structure, but just not enough that he doesn‘t understand the sucked-in original images as intersectional and problematic?

How brutal may image results be that have been shaken together from supposedly harmless material?

I asked ChatGPT the following question:

Why does AI create photos in which a doctor is choking women?

The answer was:

“It‘s important to note that AI models themselves do not have an intention or desire to create such images. Rather, they are trained on large datasets of images and other data, and can generate new images based on the patterns and associations they have learned from that data.

It is concerning and unacceptable that AI-generated images depicting violence against women exist. Such images are likely the result of biased or inappropriate training data, or the result of deliberate efforts to manipulate the AI model to produce such content.”

10 inkjet prints on Hahnemühle Photo Rag, 21 x 29,7cm, edition of 5 (+2AP)

falling bodies

As part of a performance, I asked several people during a residency in Istanbul to fall on to a mattress for me. falling bodies

I photographed the rather uncoordinated movements, that serve as a starting point for my further "case studies" arranged these poses as pairs to create a balance.

The instantaneous materialisation of fleeting bodies depict a state of uncertainty, a process of becoming and breaking apart and consequently shape-shifting into momentarily frozen sculptures.

Dompteuse de Papier

The photographic series shows separate moments in which a Din-A-4 paper is shown at the exact moment of landing. In the experiment with a conventional blank white page, a short-lived momentary pose is captured. The blank sheet itself becomes a sculptural work with a short-lived shape, caught in the act between letting go and landing. The recurring counterpart a human hand, a reminiscent of a puppet show, directs the sheet which performs a failed pointe dance.

The quite fragile material, which can normally fall over or fly away at any moment, becomes a rather cumbersome subject in the photographs.